We need to do 10x more in 2025

Capacity-building for the post-IRA electrification push.

Fifteen years ago I first joined the Obama campaign as a volunteer, but within a few days I was ready to quit my comfy job and move across the country to join as a full-time staffer. I was attending an organizing training led by Marshall Ganz, a former United Farmworkers Organizer and advisor to Cesar Chavez turned Harvard professor, and while I was already a huge fan of Barack Obama, what flipped me from “wanting to help” to essentially leaving my life behind wasn’t Obama’s stirring speeches or his vision for the country, it was learning about the campaign’s strategy and my place in it.

We wouldn’t beat them with ads or money. We didn’t have experienced campaign staff (they all worked for the other candidates). We needed to build the largest army of community organizers the country had ever seen, and win votes one relationship at a time. Marshall weaved an inspiring and compelling narrative that tied this strategy to his personal story, Barack Obama’s story, the story of the entire country, and to that particular moment in history that called us to act. I was so fired up!

Then Marshall announced our first big, official campaign objective: to recruit supporters to host “BBQs for Barack.”

What?

I was deeply confused. This was exactly the kind of wheel-spinning, navel-gazing stuff that made me wary of political activism to begin with. But as it turned out, it was a brilliant and important tactic in those early days. I later learned that events like these were ideal first-steps toward recruiting organizers because 1)if you just say “we need organizers who want to lead the largest organizing effort our country has ever seen”, the kinds of people who are likely to raise their hands are actually not the people you want, 2) it was too early in the election cycle to have people doing typical campaign activities like canvassing door to door or making phone calls, and 3) the BBQs served as a test of the host’s organizing ability. Well-attended events required careful planning and strategy, a strong existing network or community, the ability to reach and motivate people to take action, and making and keeping commitments to others.

In 2007, we were not building a movement to change the country, we were building the capacity to build that movement in 2008.

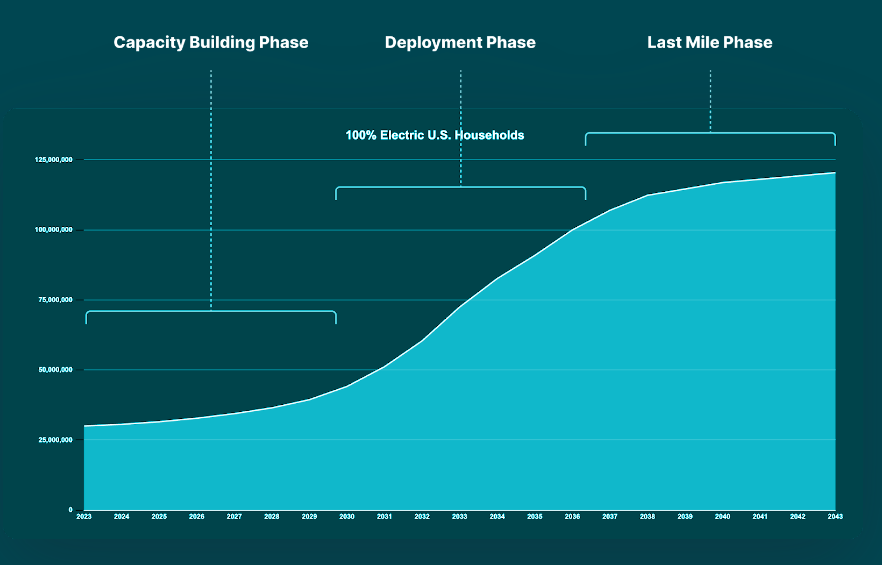

I share that anecdote because it’s clear to me now that we are very much in the capacity-building phase of the movement to electrify everything in this country. And I’m not sure we understand and appreciate that as much as we probably should - me included! I catch myself saying things like, “one biillion machines, so 50 Million per year over the next 20 years,” when I know we won’t be deploying close to 50M this year, next year, or the year after. So when you actually look at what it will take to decarbonize the economy in the next ~20 years, you realize that the task in front of us requires dramatically increasing our capacity in the years ahead. (A related phenomenon that also comes into play here is the fact that the last 10% of the work is going to be 100x harder and more stubborn than the rest, so our window to get the bulk of the work done lies in those critical middle years.)

I’m certainly no economist, but it’s intuitive to me that increasing capacity usually involves trade-offs with current production. We can’t deploy 100% of our resources and labor towards installing as many heat pumps as possible this year and build the capacity to install 10x more in 2025. Right?

Fig 1: Chart showing likely U.S. household electrification adoption curve.

Anyhow, for my part I am focusing on a project aimed at building a key piece of missing digital infrastructure for residential electrification (more on that soon!), and in order to clearly illustrate this concept for the folks I’m working with, I came up with a crude chart (Fig 1), showing what the adoption curve toward electrifying the rest of America’s 120M households might look like. I may be off by millions of homes or a few years in either direction, but the takeaway is the same: if you want to electrify every home in the U.S. over the next 20 years, and you account for the years it will take to build capacity, as well as the fact that the last ~10% of homes are going to be incredibly difficult, you end up with a period of time that is much less than 20 years during which we will need to do the vast majority of the work.

Capacity-building in the climate space takes many forms, of course, from modernizing the grid to building new battery factories, or training new workforces. I know there’s great work happening on all these fronts, all over the world. Whatever it is we’re working on, it just seems important to keep this capacity-building framework in mind, to always remember that our work today must build toward a future where can do 10x more of it in just a few years. In my experience, sometimes that means investing in strategies that might seem less impactful at first. It also requires rethinking how we measure our impact (e.g. direct GHG reductions vs. added future GHG reduction capacity).

We humans are heavily biased towards the present. We inherently value the impact we can see now more than the impact we might create in the future. To me this feels like a force of nature I have to constantly push back on in my own work. Maybe I’ll put this chart on the wall above my desk.

I’d love to hear from you! What does capacity-building look like in your climate work?